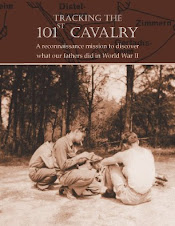

Four men, members of F Company, 101st Cavalry, squat in front of a 16-ton, M5 light tank. Someone has painted “Fightin’ Bastard” on its side. Ralph Nichols (Nick), Wilmer Fluharty (Buck), and Dominic Stolt (Dom) grin into the camera, cradling rifles in their arms. Unarmed, William Olsen (Bill) rests his left elbow on his knee, at ease. All the men wear combat helmets. It is April 1945, on the German border. On the back of this photo, taken in St. Avold, France, Buck has written, “Fightin’ Bastard Ready.” “Ready” means ready to go to war.

Buck Fluharty had sent me a dozen photos, most of which feature the Fightin’ Bastard and the four men who drove it through Germany. In one, Buck, Dom and Nick have just repaired their tank after it met a large tree head-on. Dom stands shirtless, cigarette in his hand, goggles on his forehead and dog tags hanging on his bare chest. Nick wears a rumpled shirt covered in oil and grime, and Buck, head bowed slightly, looks back at the camera over his left shoulder and grins. They are so young, and with their even features, strong chins, dimples and wavy hair, they look more like movie stars than soldiers. I had begun to love them a little already, but this photo cinched the deal. I am head-over-heels for the guys in these photos.

Within days of receiving the photos, I tracked down an address in Illinois for Dominic Stolt. I sent him a letter and copies of Buck’s photos, enclosing a self-addressed, stamped envelope. In less than two weeks, the envelope is back, a gift in my post office box. I am always excited when these envelopes return to me, even though, more often than not, they contain words similar to the ones written by Dominic Stolt’s daughter, Suzanne Stolt:

“Thank you for your letter. I lost Buck’s address, so I could not inform him that my dad passed away last year. He had a massive stroke, went into a coma and never came out of it again. Thank you for the pictures. Tell Buck I’m sorry. Dad always talked about the war and his friends.”

It’s probably silly to cry for men I never knew, who didn’t even exist for me until a few months, sometimes only a few days, ago. But I do. I cry for myself, too, because this is just one more lost opportunity.

One snapshot, taken during the wet winter of ’45, shows the Fightin’ Bastard listing to the left, buried deep in mud with two shovels planted helplessly beside it. In another, Fluharty sits atop the tank, playing his guitar. The caption reads, “Nothing going on for a spell.” He still has that guitar, which is covered with the names of the towns he saw in Europe.

It’s obvious the men think a lot of the tank; it shows up in nearly every picture. In one, only the rear of the tank is visible, as Fluharty stands there, clutching a rope that is tied to a small wagon. He makes a show of pulling the wagon, probably a child’s, in which Nick rides. Nick holds a bottle high in one hand and in the other hand he holds an umbrella, and a toy gun. Fluharty wrote: “When the captain saw us, he said ‘Fluharty, get that man back in that tank.’ Nick is now dead, but for Fluharty, and now for me, Nick survives in the memory of a playful moment captured in black and white.

The last few photos were taken in June of 1945. In one, hundreds of tanks, jeeps and armored cars line up in neat rows, covering a meadow at the foot of German mountains. In the foreground a few men pitch tents. You can’t see the faces of the men, but, since the caption reads “101st in the field after 90 days combat,” it’s easy to guess what is in their hearts. That photo is the last one in which a tank – any tank — appears. Not even Fightin’ Bastard shows up again. Tanks belonged to the war, and, in Europe, the war was over.

On June 12, 1945, in Lorsch, Germany, Buck photographs the Levasiers: Mrs. Levasier with her hair pulled back tight in a bun and arms around her daughters’ waists. Her oldest daughter, Anna, is around 20; her husband is on the Russian front. Regina, the youngest, is around 16. I learn 60 years later from Anna and Regina that the smiles are sincere. “We were never enemies. We were friends.”

Another photo, taken from inside the Levasier home, looks across the street at a neighbor’s house: a tourist photo of unfamiliar architecture, a pleasant memory for the men to share with their families at home.

Fluharty’s final photograph was taken in Heidelberg. He stands beside an open boxcar; two other men and their gear are already inside. “Never saw the tank again,” he wrote on the back. “Note smile on face, going home.”

You can see all of Fluharty’s photos and many more here.