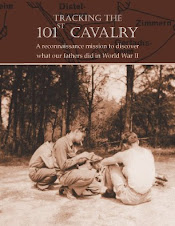

Pictured here: 2nd Lt. Zygmunt Zbrzeski

Pictured here: 2nd Lt. Zygmunt ZbrzeskiOnce I have posted something on the blog, it never occurrs to me that other people might read it and then post comments. So you can imagine my surprise yesterday when I found four comments to a post I had made two years ago.

That particular post was related to an event that took place 65 years ago, on Sunday, April 29, 1945. The 101st Cavalry came across a prisoner of war camp in Murnau, close to the Austrian border, and is considered one of the liberators of that camp. Most of the prisoners were Polish officers, and I had interviewed some of their children while writing my book. One of them was Stan Majcherkiewicz, who, along with his brother, Przemo Majcherkiewicz, had sent me a story about their father, Seweryn Majcherkiewicz. He had been captured on the outskirts of Poland in 1939. That story was the subject of a post in April 2008. To commemorate the anniversary of OFLAG-VIIA's liberation, here are the comments posted two years ago in response to that story.

Hi there, I just came across your blog and read your entry with interest. My father, George (Jerzy) Dlugopolski was also a prisoner in Murnau through the war years. He is gone now, but I remember him telling me that he was experimented upon by the Nazis doing hypothermia experiments. He said that he was put in a vat of freezing water and then in hot water. This is all he mentioned and very rarely talked about it. I have since read of other such similar experiments in other camps, but could find no information of this going on at Murnau. Would you have any information on this?I heard from some of the children of survivors that the men were treated better at Murnau than some other POW camps because of the camp’s proximity to the Swiss border. The International Red Cross would sometimes tour this camp, so the Germans used it as a model camp for PR purposes. I also have been told that, under the Nazis, "good treatment" was relative.

Thanks, Inka Glick

My Father, lieutenent Wiktor Socewicz (prisoner no. 15564 - blok G) has spent almost all the WWII war in the Murnau. He was a bandmaster (musican military). Afterwards, he was liberated, he joined to the Polish II Corps in Italy and in England. After his return to Poland in 1948, for many years he has been discriminated by the communist government (has been degradet). He worked in music education.For anyone who wants to know more about the prison at Murnau and see an amazing collection of photos, you can visit the website “Les Photos Oubliees.”

Thanks,Wiktor Daniel Socewicz, Wroclaw, Poland

My GFather Michał Mędlewski (died in 1996) was a prisoner of Murnau.My mother has a many pictures taken by soldiers. When I was a boy, GFather told me a lot of stories from Murnau about: theatre, picture of S. Marry made of box of cigarettes, history of one and only soviet army officer that commited suicide, story about good first POW camp commandant and the next-real beast etc.

Andrzej***

I also received an email from Andy Depczynski, whose grandfather, 2nd Lt. Zygmunt Zbrzeski, was a Polish supply Officer responsible for all the meat procurement for the Polish troops in Warsaw. He was captured in Warsaw near the end of September 1939 and imprisoned at Murnau for several years.My Grandfather, Wilhelm Zweck from Ceiszen, Poland, was also in Murnau for the duration of the war. He told me a story about another prisoner who made himself a German uniform out of paper?! and actually escaped. But was later caught? Anyone hear this story too? Did the prisoners play piano sometimes there? I seem to remember he

said they could. He passed away in his mid 60's. Too soon.Thank you for having this sight.

T. Nichols

Upon release from Murnau, Zbrzeski joined the 2nd Corps and continued his service in Italy and the Middle East. He was discharged in late '46 and took the Ernie Pyle to New York to meet up with his wife and daughter. They had not seen him in ten years.

Many of the emails I get from the children and grandchildren of these Polish prisoners begin with a thank you to my father and all the men he served with for liberating their fathers and grandfathers. I pass their gratitude on to as many of the members of the 101st as I can.